Wildlife, Karl Wenner’s Oregon property once discharged pollutants into a nearby lake. Waterfowl, turtles, and endangered fish now call 70 acres home.

The murmur of birdsong drowns out the roar of Karl Wenner’s vehicle as it bounces down the dirt pathways that wind through his property. This farm in southern Oregon has been growing barley for almost 100 years, but today it is home to a thriving wetland. Wenner built the wetland on 70 of his 400-acre property to help combat phosphorus contamination that spilled into the nearby Upper Klamath Lake after his land flooded each winter. The initiative has become a welcome haven for migrating and local birds that are vanishing from the area, thanks to the cooperation of a team of scientists and campaigners.

Today, this section of Lakeside Farms looks nothing like a conventional American farm. Waterfowl, pond turtles, and even endangered native fish nest among the foliage alongside rows of growing barley. Wenner brightens as he looks out at the waving cattails and wocus plants peeking through the water on a June afternoon: “This place wanted to be a wetland.”

Nowadays, Lakeside Farms’ corner looks very unlike from a conventional American farm. Near rows of growing barley, waterfowl nest with pond turtles and even critically endangered native fish. Wenner brightens as he remarks, “This place wanted to be a wetland,” as he peers out at the waving cattails and wocus plants peeking through the water on a June day.

The odds are against us. Wetlands are fast vanishing despite being regarded as “among the most productive ecosystems in the world”. Around the world, almost 80% have already disappeared. More than 95% of the wetlands in the vast Klamath basin, often referred to as the “Everglades of the west,” which spans the California-Oregon border, have been drained, redirected, or dried. Wenner, one of the land’s co-owners, believes the farm won’t remain unusual for very long. Wenner and his colleagues are enticing additional farmers and ranchers to follow in their footsteps by making an unprecedented amount of federal cash accessible through the Inflation Reduction Act and other government programmes, both of which were established under the Biden administration.

We are showing that it is feasible, said Wenner. We simply need to carry it out on a massive scale.

It's a magnificent sight to behold and create wildlife refuge

In 2021, construction on the Lakeside Farms wetland began. This involved levelling the barley fields and constructing dikes and canals to direct water flows and create small artificial nesting islands. The water, which came from a nearby natural spring, soon grew seeds for dormant marsh plants that had been dropped by birds. By the summer of 2022, the vegetation had started to clean the farm’s runoff, which had been pushed inside the banks of the ditch rather than into the lake, and feed the birds.

The plan, which was created with land capitalization and conservation in mind, removed 70 acres of the farm from use. However, Wenner claims that there are enough more government monies available and that most of his expenses have been compensated.

The Inflation Reduction Act would make over $5 billion federal cash available to support projects on agricultural land that address conservation issues, in addition to state and municipal financing programmes. Wenner claims that the advantages have been virtually instantaneous.

Wetlands act as a kind of natural sponge, absorbing up dangerous pollutants and minerals before they enter the watershed. Cropland owned by Lakeside Farms, located between Upper Klamath Lake and a motorway, leached a lot of phosphorus last February, around five times more than was permitted by laws. The wetland filtered the silt back to acceptable levels in only a few short months. Wenner stated, “You set the stage and mother nature takes over.” It is simply a magnificent sight to behold.

Wenner is certain that the decision has benefited business. The farm is no longer breaking the law, and a plan to turn additional portions of its property into rotational marsh will allow it to become organic, resulting in “a much higher price for the crop.”

The project is being undertaken at a crucial moment for the area, which coexists with hundreds of farms and ranches and one of the biggest watersheds in the western US. Despite having a high biodiversity, the region has deteriorated as crops and cattle ranches have replaced marshes and lakebeds. The Klamath basin is becoming drier and hotter as a result of the climate crisis, stressing out both farmers and animals. The number of migratory bird populations has drastically decreased, from a peak of almost 5 million birds recorded in 1958 to approximately 93,000 birds reported last year.

Plans to remove four dams from the Klamath River, the largest dam removal project in US history, are giving many reason for hope as they move the ecosystem one step closer to recovery. But additional answers will be required. One of the county’s largest ecosystems has the potential to resume operating now that the dams are being removed, according to Wenner. It is a disturbed, broken system, but it can be fixed.

There are difficulties with the work. “Our biggest challenge is where water is available to manage wetlands,” said Ed Contreras, coordinator of the Intermountain West Joint Venture, a group devoted to creating public-private alliances to maintain bird habitats. The Lakeside Farms initiative, he said, was a crucial case study. I now consider this programme as a pilot, he declared. There was optimism about the potential for growth throughout the area, he added, but “to scale that up, a lot of people will need to come together and think big picture.”

The same difficulties are being faced by Paul Botts thousands of miles away. He is keen to spread the use of what he terms “smart wetlands” across profitable agricultural belts as the executive director of the Wetlands Initiative, a non-profit conservation organisation in Chicago, and envisions a day when they will be as widespread as any other farming technique. The end aim is for there to be wetlands in every farm field in the Midwest when my children or grandkids are driving through it, he added. In his opinion, a greater dependence on wetlands will be necessary to achieve conservation objectives and will also stabilise food providers in the face of uncertainty.

Farmers are experiencing the effects of the changing climate, he claimed. “Reintroducing a few small, dispersed wetlands to our landscape is one of the best things we can do to adapt ourselves to that changing climate.”By storing water for dry periods and reducing the intensity of floods, these natural systems lessen the impact of climatic calamities. “We view smart wetlands as an excellent example of a big-picture climate adaptation solution,” Botts continued.

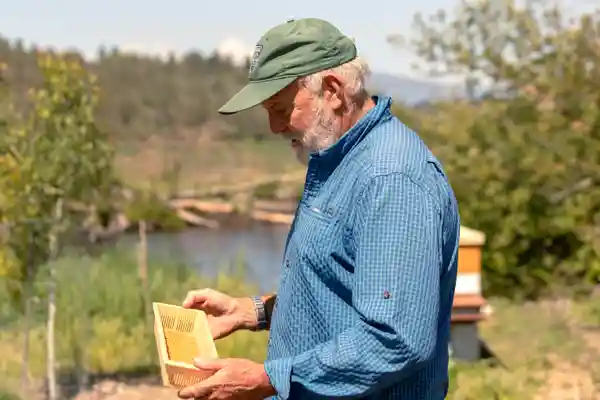

Wenner is checking on his bees back in Klamath. As the insects casually come and go, he takes out a tiny dish from one of his boxes hives and marvels at the pollen that has been harvested. He will soon ship it to a lab in Belgium that examines the materials the bees have collected in order to provide him with information on what is going to seed at Lakeside Farms. There are a tonne of plants growing outside, and the bees will identify them for us, he continued. The outcomes have already been thrilling. The once-monocultured terrain is now teeming with biodiversity, including both plants and animals.

Wenner sheds tears as he discusses the adjustment. A plan to comply with the law grew into an opportunity. He remarked, “I read the news, and it’s just one environmental catastrophe after another.” But I’ve always believed that we could be capable of solving this problem. Now I know you can,” he said. Wenner wants to give the natural systems a chance. We simply need to devise a method for doing it.